Cambodian diaspora in Japan share their histories

Cambodian diaspora in Japan share their histories

日本に住むカンボジア系移民が伝える歴史

អាណិកជនខ្មែរនៅប្រទេសជប៉ុនរៀបរាប់រឿងរ៉ាវអតីតកាលរបស់ពួកគេ

December 2019 - October 2022

Japan, Cambodia

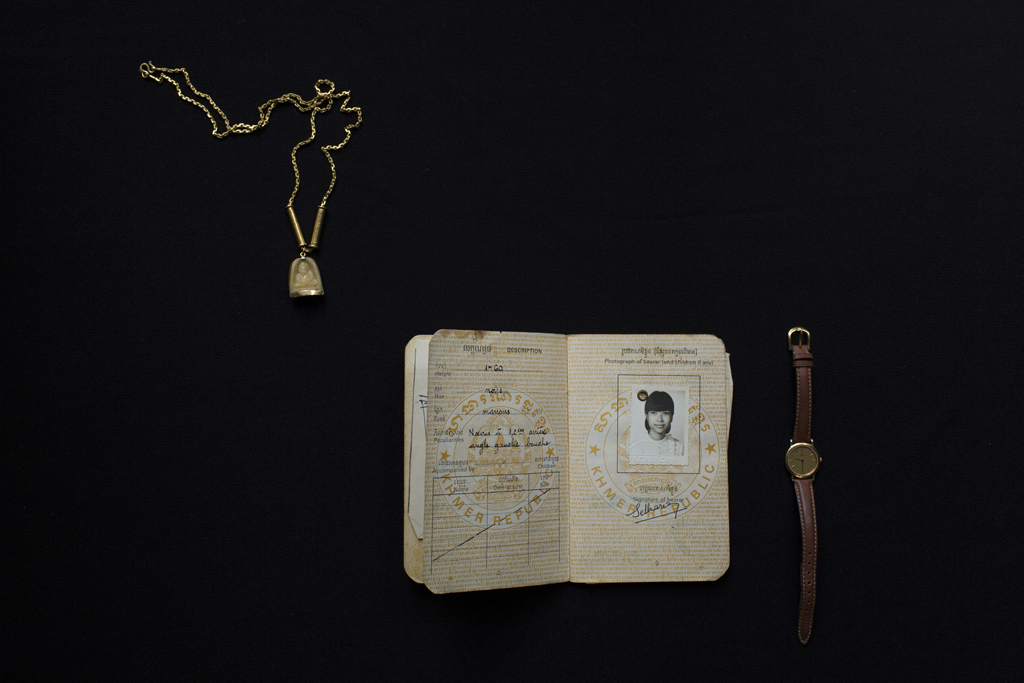

Artist Kim Hak worked with Japan's Cambodian community on this project. TRAVEL DOCUMENT FOR ALIEN AND GROUP FAMILY PHOTO AT NARITA AIRPORT. Photograph by Kim Hak.

写真家のキム・ハクは日本のカンボジア人コミュニティと共にこのプロジェクトに取り組みました。外国人用の渡航書類と成田空港で撮影した家族集合写真。 撮影:キム・ハク

សិល្បករ គឹម ហាក់ បានធ្វើការជាមួយសហគមន៍ខ្មែរនៅប្រទេសជប៉ុនសម្រាប់គម្រោងនេះ។ ឯកសារសម្រាប់ឆ្លងដែនមកប្រទេសជប៉ុន និងរូបថតក្រុមគ្រួសារនៅព្រលានយន្តហោះណារីតា រូបថតដោយ គឹម ហាក់

Cambodian diaspora in Japan share their histories

Cambodian diaspora in Japan share their histories

日本に住むカンボジア系移民が伝える歴史

អាណិកជនខ្មែរនៅប្រទេសជប៉ុនរៀបរាប់រឿងរ៉ាវអតីតកាលរបស់ពួកគេ

December 2019 - October 2022

Japan, Cambodia

Many Cambodians were forced to flee their country to escape oppression, massacre and war under the Khmer Rouge regime of the 1970s. They left their homes with few possessions: only the most valuable or practical items were brought along on this difficult journey. From 1975 to 1997 around 260,000 Cambodians resettled all over the world.

1970年代のクメール・ルージュ政権下で起きた抑圧、大量虐殺、戦争から逃れるために、多数のカンボジア人がやむなく祖国を離れました。家を出た時の持ち物は僅かです。一番大切な物や実用的な物だけ携えて困難な旅に出ました。1975年から1997年までにおよそ26万人のカンボジア人が世界各地に移住しました。

Rei Foundation Limited បានសហការជាមួយសិល្បករថតរូបសញ្ជាតិកម្ពុជា គឹម ហាក់ ជាថ្មីម្តងទៀត សម្រាប់គម្រោងរស់រាន ជំពូក៤។ «រស់រាន ជំពូក៤» គឺជាគម្រោង និងពិព័រណ៍រូបថតដែលបានតាំងបង្ហាញនៅទីក្រុងតូក្យូ និងយូកូហាម៉ា ដោយរំលេចស្នាដៃរូបថតប្រមាណ៤០សន្លឹក អមជាមួយនឹងអត្ថបទដែលបរិយាយអំពីរបស់របរផ្ទាល់ខ្លួនរបស់អ្នកដែលបានភៀសខ្លួនចេញពីប្រទេសកម្ពុជា អំឡុងពេល និងបន្ទាប់ពីសង្គ្រាមស៊ីវិលក្នុងទសវត្សរ៍ឆ្នាំ១៩៧០ ហើយដែលសព្វថ្ងៃ ពួកគេកំពុងរស់នៅក្នុងទឹកដីប្រទេសជប៉ុន។

ប្រជាជនកម្ពុជាជាច្រើននាក់ត្រូវបង្ខំចិត្តភៀសខ្លួនចេញពីមាតុភូមិរបស់ខ្លួន ដើម្បីគេចចេញពីការគាបសង្កត់ ការសម្លាប់រង្គាល និងភ្លើងសង្រ្គាម ក្រោមរបបខ្មែរក្រហមនាទសវត្សរ៍ឆ្នាំ ១៩៧០។ ពួកគេបានចាកចេញពីផ្ទះសម្បែង ជាមួយនឹងរបស់របរផ្ទាល់ខ្លួនបន្តិចបន្តួចប៉ុណ្ណោះ។ ពួកគេយកតែរបស់ដែលមានតម្លៃបំផុត ឬសម្ភារដែលអាចប្រើការបានសម្រាប់ដំណើរដ៏សែនលំបាកនេះ។ មានប្រជាជនកម្ពុជាប្រមាណ ២៦ ម៉ឺននាក់ បានតាំងទីលំនៅនៅពាសពេញពិភពលោក គិតពីចន្លោះឆ្នាំ ១៩៧៥ ដល់ ១៩៩៧។

កើតក្នុងឆ្នាំ១៩៨១ លោក គឹម ហាក់ ចាប់អារម្មណ៍នឹងប្រវត្តិសាស្ត្រនៃសម័យកាល និងរឿងរ៉ាវដែលបានកើតឡើងក្នុងជំនាន់ឪពុកម្តាយលោក។ ក្នុងឆ្នាំ២០១៤ លោកចាប់ផ្តើមសួរនាំអ្នកដែលរស់រានពីរបបខ្មែរក្រហម ហើយចងក្រងអំពីរបស់របរ និងរឿងរ៉ាវដែលផ្សារភ្ជាប់នឹងរបស់អស់ទាំងនោះ។ គម្រោង «រស់រាន» ផ្តើមឡើងដោយសារការសម្ភាសឪពុកម្តាយលោកដែលរស់នៅក្នុងខេត្តបាត់ដំបង ប្រទេសកម្ពុជា ហើយពីពេលនោះមក គម្រោងនេះក៏បានវិវឌ្ឍទៅជាជំពូកៗ ពីទីក្រុងប្រ៊ីសប៊ែន ប្រទេសអូស្ត្រាលីក្នុងឆ្នាំ២០១៥ និងនៅទីក្រុងអូកខ្លិន ប្រទេសនូវែលហ្សេឡង់ ក្នុងឆ្នាំ២០១៨ (ដោយទទួលការគាំទ្រពី Rei Foundation ផងដែរ) បង្កើតឱ្យមានការសន្ទនារវាងមនុស្សម្នាក់ទៅមនុស្សម្នាក់ និងរវាងជំនាន់មួយទៅជំនាន់មួយទៀត អំពីបទពិសោធន៍របស់អ្នកដែលនៅរស់រាននៅក្នុងសហគមន៍ទាំងអស់នោះ។

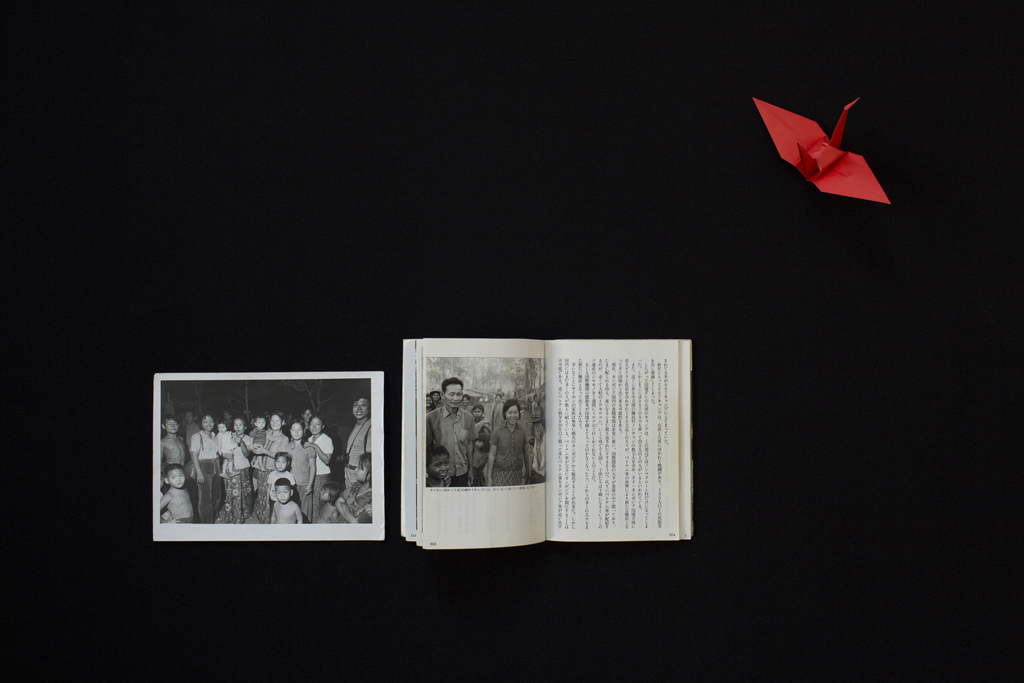

Belongings of Heng Say Kim: photos at Camp 07 and article, Help, which was illustrated with photographs by Japanese photographer Mitome Tadao, who documented the atrocities being committed by the Khmer Rouge upon Cambodians. Photo by Kim Hak.

ヘン・サイキムの所持品: キャンプ07で撮影された写真と、日本人写真家三留理男の写真を併載した記事「Help」。三留理男はクメール・ルージュがカンボジア人に対して行った残虐行為を記録しました。 写真:キム・ハク

កម្មសិទ្ធិរបស់ ហេង សាយគឹម៖ រូបថតនៅជំរំទី០៧ និងអត្ថបទដែលមានចំណងជើងថា «ជួយផង» អមដោយរូបភាពជារូបថត ថតដោយជនជាតិជប៉ុន Mitome Tadao ដែលបានចងក្រងអំពីអំពើឃោរឃៅរបស់ទាហានខ្មែរក្រហមមកលើប្រជាជនកម្ពុជា។ រូបថតដោយ គឹម ហាក់

ក្នុងឆ្នាំ២០២០ លោក គឹម ហាក់ បានធ្វើដំណើរទៅប្រទេសជប៉ុនតាមរយៈកម្មវិធី fellowship មួយ ក្នុងគោលបំណងជួប និងបង្កើតស្នាដៃជាមួយសហគមន៍ខ្មែរក្នុងប្រទេសជប៉ុន ដែលគម្រោងនេះគាំទ្រដោយមជ្ឈមណ្ឌលអាស៊ីនៃមូលនិធិជប៉ុន។ គម្រោង «រស់រាន ជំពូក៤» ចងក្រងឡើងដោយពណ៌នាអំពីរឿងរ៉ាវប្រជាជនខ្មែរ១៣គ្រួសារ ដែលក្នុងនោះរួមមាន៖ អតីតនិស្សិតអន្តរជាតិដែលមិនអាចត្រឡប់ទៅមាតុភូមិពួកគេវិញបាន ដោយកត្តាចលាចលនៅក្នុងប្រទេសកម្ពុជាក្នុងទសវត្សរ៍ឆ្នាំ១៩៧០ និងអ្នកដែលបានមកដល់ប្រទេសជប៉ុនក្នុងទសវត្សរ៍ឆ្នាំ១៩៨០ ក្នុងនាមជាជនភៀសខ្លួនដោយសាររបបខ្មែរក្រហម។ របស់របរផ្ទាល់ខ្លួនរបស់ពួកគេដូចជា៖ នាឡិកាដៃ រូបថតគ្រួសារ និងក្រវិល គឺប្រដូចទៅនឹងសំពៅមួយដែលផ្ទុកទៅដោយអនុស្សារីយ៍អំពីស្រុកកំណើត ដំណើរភៀសខ្លួន និងបទពិសោធន៍របស់ពួកគេជានិរទេសជន។ គឹម ហាក់ បានសាកសួរគ្រួសារនីមួយៗនៅកាណាហ្គាវ៉ា តូក្យូ និងសៃតាម៉ា។ ដំបូង លោកបានសម្ភាសពួកគេ រួចលោកបានថតរូបរបស់របរសំខាន់ៗដែលពួកគេបានរក្សាទុក ក្នុងដំណើរឆ្ពោះទៅការតាំងទីលំនៅសាជាថ្មី។ អមជាមួយនឹងការថតរូប គឹម ហាក់ ក៏បានសរសេរអត្ថបទដែលរៀបរាប់អំពីរបស់របរ ភ្ជាប់ទៅនឹងរឿងរ៉ាវមនុស្ស។

ペン・セタリンの物語

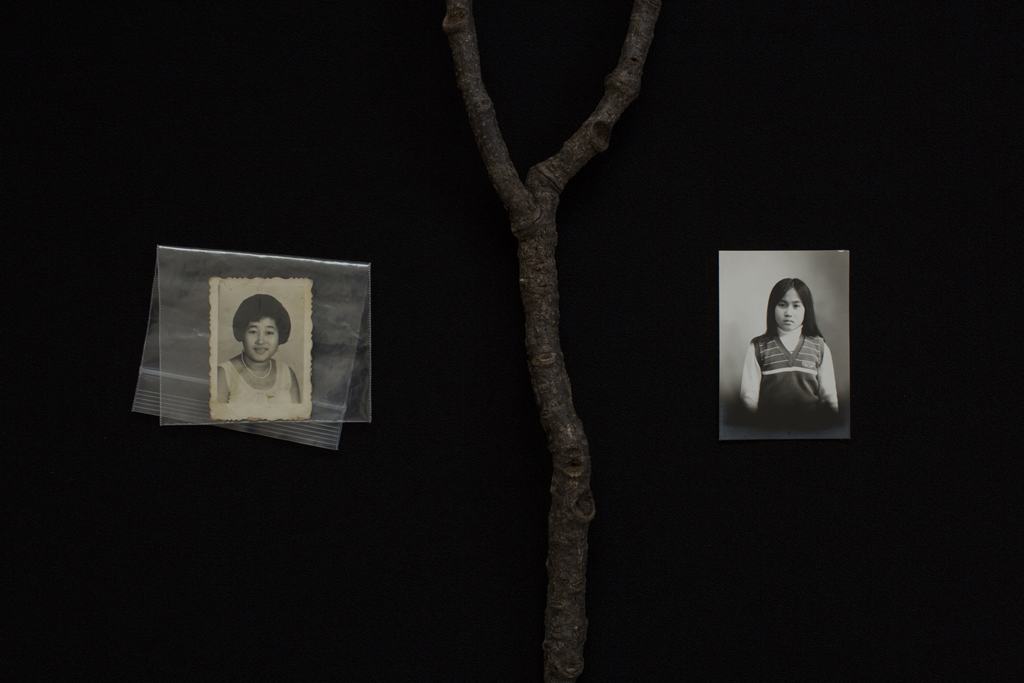

Penn Setharin grew up in Phnom Penh, the oldest of eight siblings and an excellent student – her mother was a teacher. In 1974, Setharin became the first woman in Cambodia to receive a scholarship to study in Japan. After a year, she heard she could continue studying in Japan and wrote to her mother with the news, but heard nothing back, which was worrying. Eventually, Japanese newspapers began to report that Cambodia had fallen under the Khmer Rouge.

Between 1975 and 1979, Setharin volunteered in refugee camps as a translator with a group of Japanese volunteers. It was during this time she found a cousin and three of her siblings, and, confirming her dream, she learnt that her remaining four siblings and her parents had all died. She brought her surviving siblings to live in Japan together. Setharin took part in Kim Hak’s project, sharing her story and important objects. One image shows Setharin reading, with papayas, in reference to her premonition, sitting in the background. Setharin remains a scholar, dividing her time between Japan and Cambodia, where teaches Anthropology and Methodology of Translation at Royal University of Phnom Penh.

ペン・セタリンはプノンペン育ちで8人きょうだいの長子です。成績優秀で母は教師でした。1974年にセタリンはカンボジア人女性で初めて日本で勉強をする奨学金を授与されました。一年留学した後、日本で勉学を続ける事ができると聞き、その知らせを母に伝えるために手紙を書きましたが、母から返事がなく心配しました。その後、カンボジアはクメール・ルージュの支配下に置かれたと日本の新聞が報道するようになります。

1975年から79年まで、セタリンは日本人ボランティアと共に難民キャンプで通訳ボランティアをしました。この間にいとこ1人ときょうだい3人が見つかり、夢で見た通りきょうだい4人と両親が亡くなった事を知りました。生き残った3人のきょうだいと日本で一緒に暮らすため、セタリンは彼らを呼び寄せます。セタリンはキム・ハクのプロジェクトに参加し、彼女の物語と大切にしていた所持品を、作品を見る人と分かち合います。1枚の写真ではセタリンは本を読んでいます。彼女の予感を象徴して背景にパパイヤがあります。セタリンは現在も教授を務め、日本とカンボジアを行き来しながら王立プノンペン大学で文化人類学と翻訳方法論を教えています。

រឿងរ៉ាវរបស់លោកស្រី ស្វាយ សេដ្ឋារិន

និស្សិតខ្មែរជាច្រើនដែលរស់នៅប្រទេសជប៉ុនកាន់ទិដ្ឋាការសិក្សា នៅពេលដែលខ្មែរក្រហមចូលគ្រប់គ្រងប្រទេស។ ពួកគេយល់ថាខ្លួនកំពុងជាប់គាំងនៅលើទឹកដីបរទេស ជាទីកន្លែងដែលពួកគេគ្រោងថានឹងរស់នៅត្រឹមរយៈពេលបណ្តោះអាសន្នប៉ុណ្ណោះ។

ធំដឹងក្តីឡើងនៅរាជធានីភ្នំពេញ លោកស្រី ប៉ែន សេដ្ឋារិន ជាកូនស្រីច្បងនៃគ្រួសារដែលមានកូនប្រាំបីនាក់ និងជាសិស្សពូកែមួយរូបផង។ លោកស្រីមានម្តាយធ្វើជាគ្រូបង្រៀន។ ក្នុងឆ្នាំ១៩៧៤ យុវនារីសេដ្ឋារិនក្លាយជាស្ត្រីខ្មែរទីមួយដែលទទួលបានអាហារូបករណ៍ទៅសិក្សាក្នុងប្រទេសជប៉ុន។ រៀនបានមួយឆ្នាំ នាងឮថា នាងអាចបន្តការសិក្សាក្នុងប្រទេសជប៉ុនបន្តទៀត នាងក៏បានសរសេរសំបុត្រទៅជម្រាបម្តាយនាងអំពីដំណឹងនេះ ប៉ុន្តែនាងមិនបានទទួលដំណឹងឆ្លើយតបវិញឡើយ ជាហេតុធ្វើឱ្យនាងព្រួយបារម្ភ។ ក្រោយមក កាសែតជប៉ុនចាប់ផ្តើមរាយការណ៍ថា ប្រទេសកម្ពុជាបានធ្លាក់ក្រោមរបបដឹកនាំរបស់ខ្មែរក្រហម។

នៅក្នុងពេលវេលាដ៏សែនលំបាកនេះ នាងបាត់ដំណឹងសូន្យឈឹងពីគ្រួសារនាង ប៉ុន្តែនាងបានដឹងអំពីស្ថានការណ៍ដែលកំពុងកើតឡើងតាមរយៈយល់សប្តិដែលហាក់នៅនឹងមុខ។ ក្នុងយល់សប្តិមួយនោះ នាងកំពុងបេះល្ហុងនៅផ្ទះនាងនៅទីក្រុងភ្នំពេញ។ ភ្លាមៗនោះ នាងស្ថិតក្នុងសភាពភាន់ភាំង ហើយទាហានខ្មែរក្រហមក៏ចាប់ផ្តើមបាញ់សម្រុក។ ក្នុងយល់សប្តិមួយទៀត នាងសុបិនឃើញថានាងជាអ្នកកាសែតមួយរូបដែលកំពុងសម្ភាសម្តាយនាង។ នាងបានសាកសួរម្តាយនាងថា តើគាត់បានបាត់បង់កូនប៉ុន្មាននាក់ក្នុងអំឡុងសម័យខ្មែរក្រហម ហើយម្តាយនាងក៏ឆ្លើយថា គាត់បានបាត់បង់កូនចំនួនបួននាក់ ហើយកូនបីនាក់ផ្សេងទៀតរស់រាននៅឡើយ។

ក្នុងចន្លោះឆ្នាំ ១៩៧៥ និង១៩៧៩ សេដ្ឋារិនបានធ្វើការស្ម័គ្រចិត្តក្នុងជំរំជនភៀសខ្លួនជាអ្នកបកប្រែជាមួយនឹងក្រុមស្ម័គ្រចិត្តជនជាតិជប៉ុន។ គឺអំឡុងពេលនេះហើយដែលនាងបានជួបនឹងបងប្អូនជីដូនមួយម្នាក់ និងបងប្អូនបង្កើតបីនាក់របស់នាង ដែលបញ្ជាក់ដូចក្នុងសុបិន។ នាងបានដឹងថា បងប្អូនបួននាក់ផ្សេងទៀត និងឪពុកម្តាយនាងបានស្លាប់ទាំងអស់។ នាងបានយកបងប្អូនដែលនៅរស់រានទាំងបីនាក់ ទៅរស់នៅក្នុងប្រទេសជប៉ុនជាមួយគ្នា។ លោកស្រី សេដ្ឋារិន បានចូលរួមក្នុងគម្រោងរបស់សិល្បករ គឹម ហាក់ ដោយលោកស្រីបានចែករម្លែករឿងរ៉ាវរបស់លោកស្រី និងរឿងរ៉ាវអំពីរបស់របរសំខាន់ៗមួយចំនួនផងដែរ។ រូបមួយបង្ហាញពីលោកស្រីកំពុងអានសៀវភៅ ដោយមានរូបល្ហុងពីរផ្លែលើផ្ទាំងខ្មៅខាងក្រោយ តំណាងឱ្យប្រផ្នូលរបស់លោកស្រី។ លោកស្រី សេដ្ឋារិន ជាអ្នកប្រាជ្ញមួយរូប ដែលបែងចែកពេលវេលាទាំងនៅជប៉ុនផង និងកម្ពុជាផង ដោយលោកស្រីបង្រៀនមុខវិជ្ជានរវិទ្យា និងវិធីសាស្ត្រនៃការបកប្រែនៅសាកលវិទ្យាល័យភូមិន្ទភ្នំពេញ។

ソック・ポーンの物語

រឿងរ៉ាវរបស់ លោកស្រី សុខ ភ័ណ

របស់របរផ្ទាល់ខ្លួនរបស់សុខ ភ័ណ ឆ្លុះបញ្ចាំងតថភាពនៃភាពឧស្សាហ៍នៃអ្នកដែលរស់នៅក្នុងជំរំជនភៀសខ្លួន បន្ទាប់ពីរបបខ្មែរក្រហមបានដួលរលំទៅ។ កញ្ញា ភ័ណបានក្លាយជានារីជំទង់មួយរូប ខណៈនៅជំរំជនភៀសខ្លួន នាងដេរឈុតសម្លៀកបំពាក់ (ដូចបង្ហាញនៅរូបខាងលើ) ដើម្បីឱ្យស៊ីគ្នានឹងរូបរាងដ៏តូចរបស់នាង។

យុវនារី ភ័ណ បានរៀបការនៅអាយុ១៨ឆ្នាំ ហើយប្តីរបស់នាងមានរបរថតចម្លងកាសែតចម្រៀងចាស់ៗ ដើម្បីយកទៅលក់នៅជំរំ។ ក្នុងឆ្នាំ ១៩៩៧ ប្តីប្រពន្ធមួយគូនេះបានទទួលដំណឹងថា ពួកគេអាចផ្លាស់ទីទៅរស់នៅប្រទេសជប៉ុន។ ប្តីរបស់ភ័ណប្រឹងស្ពាយកាសែតចម្រៀងចម្លងចាស់ៗប្រហែល៣០០មកតាមខ្លួន ដោយសង្ឃឹមថាអាចបន្តរបរខ្លួននៅប្រទេសជប៉ុន ប៉ុន្តែប្រជាជនខ្មែរនៅប្រទេសជប៉ុនលែងមានចំណូលចិត្តស្តាប់បទចម្រៀងខ្មែរចាស់ៗទៀតហើយ ដូច្នេះ របរនេះមិនអាចដំណើរការទៅបានដោយជោគជ័យឡើយ។ ទោះជាបែបនេះក្តី ប្តីប្រពន្ធមួយគូនេះបន្តរក្សាកាសែតចម្រៀងនៅផ្ទះរបស់ខ្លួន ហើយមិនធ្លាប់គិតចង់បោះវាចោលឡើយ។

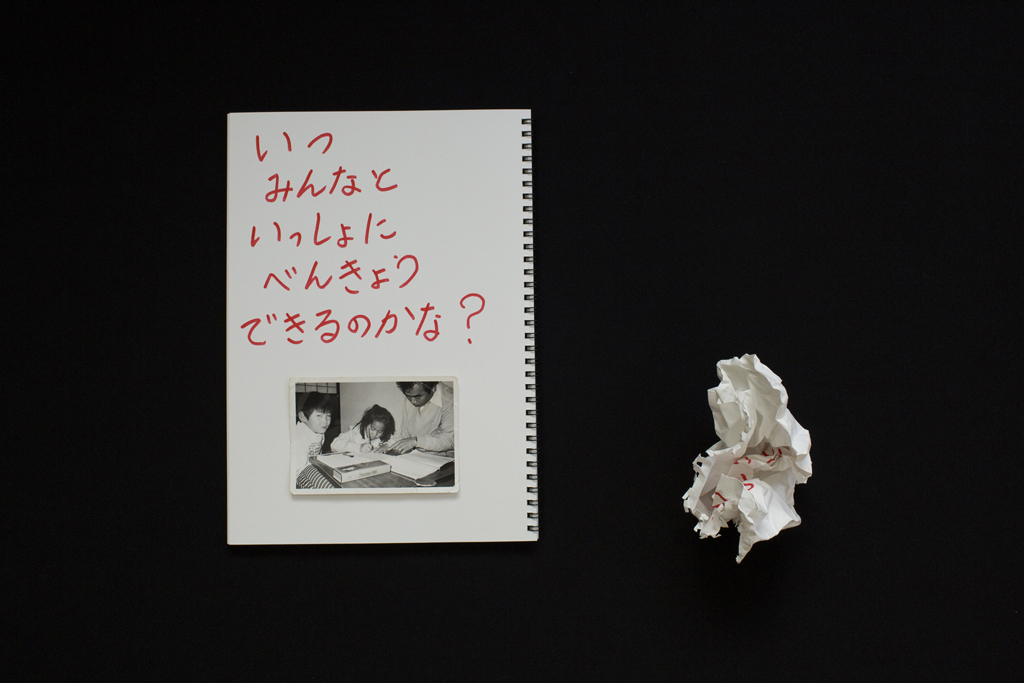

萩原カンナの物語

រឿងរ៉ាវរបស់ ហាហ្គីវ៉ារ៉ា ខាន់ណា

ហាហ្គីវ៉ារ៉ា ខាន់ណា ដែលមានឈ្មោះជាខ្មែរថា ជាង សេងទក្ខិណា នៅជាកុមារីនៅឡើយ ពេលដែលទីក្រុងភ្នំពេញធ្លាក់ក្រោមការគ្រប់គ្រងរបស់ខ្មែរក្រហមក្នុងឆ្នាំ១៩៧៥។ ក្នុងអំឡុងកុមារភាព នាងត្រូវបានបំបែកចេញពីគ្រួសារ និងត្រូវបង្ខំឱ្យធ្វើការក្នុងកងកុមារ ហើយត្រូវធ្វើដំណើរដ៏សែនឆ្ងាយទម្រាំដល់ជំរំ រួចនាងបានជួបជុំជាមួយសមាជិកគ្រួសារវិញ។ នាងបានឃើញផ្ទាល់ភ្នែកនូវការឈឺចាប់ដ៏ខ្លោចផ្សានៃជនភៀសខ្លួនដទៃទៀតក្នុងអំឡុងពេលនោះ។ ក្រោយមក មីងរបស់នាងដែលសព្វថ្ងៃកំពុងរស់នៅប្រទេសជប៉ុន បានជួបនាង រួចនាំនាងមករស់នៅប្រទេសជប៉ុន។

គ្រួសារខ្មែរដែលមកប្រទេសជប៉ុនក្នុងនាមជាជនភៀសខ្លួនតែងតែជួបនឹងបញ្ហាការមើលងាយ ដោយសារតែ ពួកគេព្យាយាមរកផ្ទះស្នាក់នៅ ការងារ និងការសិក្សាផង។ គ្រួសាររបស់ខាន់ណាស្ថិតក្នុងចំណោមគ្រួសារខ្មែរដំបូងបង្អស់ដែលមកជ្រកកោនក្នុងប្រទេសជប៉ុន នៅខេត្តតូតូរិ។ ពីដំបូងឡើយ នៅពេលដែលខាន់ណា និងបងប្អូនជីដូនមួយនាងព្យាយាមចូលរៀននៅសាលា សាលាមិនអនុញ្ញាតិឱ្យពួកគេចុះឈ្មោះចូលរៀនទេ ដោយហេតុថា ពួកគេគឺជាជនភៀសខ្លួន។ រឿងរ៉ាវនេះត្រូវបានចុះផ្សាយក្នុងទំព័រកាសែត និងផ្សព្វផ្សាយតាមទូរទស្សន៍។ ខាន់ណាចាំថា ពួកគេត្រូវទៅសាលាខេត្តដើម្បីជជែកអំពីបញ្ហានេះ។ ចុងក្រោយ គេបានអនុញ្ញាតឱ្យពួកគេចូលរៀន ប៉ុន្តែវាជាពេលវេលាដែលប៉ះទង្គិចផ្លូវចិត្តមួយសម្រាប់ខាន់ណា។ «ជាជនភៀសខ្លួន ពួកយើងបានឆ្លងកាត់ភ្លើងសង្គ្រាម និងទុក្ខលំបាកជាច្រើន មកដល់ដីថ្មី ពួកយើងសុំត្រឹមតែក្តីសុខទេ។»

គម្រោង «រស់រាន ជំពូក៤» របស់សិល្បករ គឹម ហាក់ បានដាក់តាំងបង្ហាញនៅ Spiral Garden ក្នុងទីក្រុងតូក្យូ ចាប់ពីថ្ងៃទី១៩ ដល់ថ្ងៃទី ២៨ ខែសីហា និងនៅ Elevated Studio-A Gallery ក្នុងទីក្រុង យូកូហាម៉ា ចាប់ពីថ្ងៃទី ០៩ ដល់ថ្ងៃទី ២៥ ខែកញ្ញា ឆ្នាំ២០២២។ ជាមួយគ្នានឹងការបើកកម្មវិធីយ៉ាងរលូន ពិព័រណ៍នេះនាំមកជាមួយនូវកម្មវិធីផ្សេងៗ ដែលក្នុងនោះមាន ការសម្តែងសិល្បៈវប្បធម៌ខ្មែរ វេទិកាសាធារណៈ សិក្ខាសាលាជាមួយនឹងយុវជន និងទស្សនកិច្ចពិព័រណ៍សម្រាប់អ្នកសារព័ត៌មានក្នុងស្រុក។

ពិព័រណ៍នេះបានផ្តល់ឱកាសដល់សហគមន៍ខ្មែរក្នុងប្រទេសជប៉ុន និងទស្សនិកជនជប៉ុន ឱ្យចូលរួមក្នុងកិច្ចសន្ទនាអំពីបទពិសោធន៍ចម្រុះនៃជនអន្តោប្រវេសន៍សញ្ជាតិកម្ពុជាក្នុងអំឡុងពេល និងក្រោយរបបខ្មែរក្រហមបានដួលរលំទៅ។ ក្តីសង្ឃឹមរបស់ Rei Foundation Limited គឺកិច្ចសន្ទនាទាំងនេះនឹងជួយយើងទាំងអស់គ្នាធ្វើដំណើរឆ្ពោះទៅមុខដោយការយោគយល់អធ្យាស្រ័យ និងទទួលស្គាល់កាន់តែខ្លាំងឡើង មិនថាគ្រប់គ្នាមកពីណា ឬប្រកាន់ខ្ជាប់នូវវប្បធម៌អ្វីឡើយ។

Return to Projects