Objects, Memory, and Peacebuilding by Dody Wibowo

8 October 2019

There is no single truth about the past. However, as Rei Foundation scholar Dody Wibowo argues, we are at times exposed to and asked to believe in a single definitive version of history.

Wibowo explores the complex construction of his own understanding of traumatic historic events, an understanding primarily developed through intense experiences at government-run museums, first in his home country Indonesia, and then in Cambodia.

Wibowo explores the complex construction of his own understanding of traumatic historic events, an understanding primarily developed through intense experiences at government-run museums, first in his home country Indonesia, and then in Cambodia.

Using the lens of peace education, he asks us to consider the motives and strategies of such museums, and suggests a way forward through museum practices that contribute to peacebuilding.

There is a particular event in Indonesian history that I can recall with remarkable clarity due to the extensive memory creation process mobilised by the Government of Indonesia during the Soeharto era. This event is the killing of six military generals by the Indonesian Communist Party members (Partai Komunis Indonesia/PKI) on 30 September 1965. Although it happened before I was born, I learned about the killing through at least three different media: in history class at school, a film, and a museum.

I grew up in Indonesia in the ’80s and studied in an education system that employed a top-down approach. At that time, there was no space afforded for students to develop critical thinking skills. My teacher taught me about the killing based on the official history book, whose content had been approved by the Ministry of Education, and which was written by the Government of Indonesia.

As a student, I never questioned the truth of the story because there was no alternative information available to me; all information was controlled by the government. Therefore, I believed their account to be the truth; the only truth.

As a student, I never questioned the truth of the story because there was no alternative information available to me; all information was controlled by the government. Therefore, I believed their account to be the truth; the only truth.

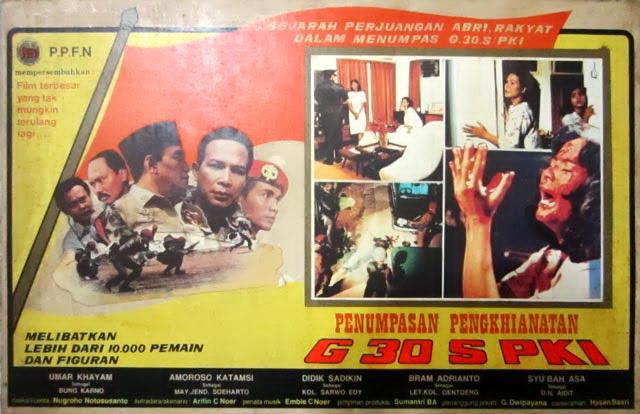

In 1984 the Indonesian government, under Soeharto leadership, produced a movie titled Pengkhianatan G30S PKI, or Betrayal of Indonesia Communist Party (lobby card, pictured left). This movie aired during prime time on all Indonesian TV stations every 30 September. Over the course of almost four hours, this film shows many scenes wherein the PKI (communist) members violently tortured the generals before they killed them.

Because this movie was categorised as a history lesson, I watched it at home, as well as in the cinema with my primary school classmates. The continuous exposure to this movie means I still clearly remember some of the violent scenes today. The movie stopped being aired on television after the fall of Soeharto in 1998.

This memory creation regarding the history of 30 September was strengthened by my visit to the Pancasila Sakti Monument, a museum built by the government to commemorate the event. I visited this museum as part of my junior high school’s study tour in 1994, my first and only visit. Built in the precise location where the generals were tortured, killed, and buried, this museum displays dioramas and objects related to the event.

My friends and I went through different rooms alone, unaccompanied by a museum guide. There is a specific display that I remember clearly, even now: a life-sized diorama that shows PKI members torturing the generals. While viewing this diorama, we could hear a narrative of the event told by two voices. The voices of the narrators have a 60’s era timbre, emphasising the time when the event occurred. Another recording featured the sound of the cheering voices of the PKI supporters, similar to the sounds I recall hearing in the movie.

My friends and I went through different rooms alone, unaccompanied by a museum guide. There is a specific display that I remember clearly, even now: a life-sized diorama that shows PKI members torturing the generals. While viewing this diorama, we could hear a narrative of the event told by two voices. The voices of the narrators have a 60’s era timbre, emphasising the time when the event occurred. Another recording featured the sound of the cheering voices of the PKI supporters, similar to the sounds I recall hearing in the movie.

I also remember that there was nowhere in the museum for visitors to contemplate what they had seen after visiting the traumatising exhibition. Therefore, I went home with an uneasy feeling, and without the chance to express my emotions. Even my teacher did not open a dialogue to discuss what we had seen at the museum.

This experience of seeing the diorama on the site where the actual event happened, accompanied by a narrative that resounded with history, stimulated all my senses to make me feel as though I was there at the exact time and place when the event was happening. The visit to this museum confirmed the story I had learned from school, and the film. It affected my understanding of the event, and my belief in the truth of the story provided by the government became stronger.

This experience of seeing the diorama on the site where the actual event happened, accompanied by a narrative that resounded with history, stimulated all my senses to make me feel as though I was there at the exact time and place when the event was happening. The visit to this museum confirmed the story I had learned from school, and the film. It affected my understanding of the event, and my belief in the truth of the story provided by the government became stronger.

It was not long before I felt overwhelmed by the information I was receiving.

In 2014 I taught in Cambodia, where I visited both the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, and the Choeung Ek Genocide Center in Phnom Penh as part of class activities for my students. Before my visit, I was unaware of what I would see in those museums. I was just like any ordinary visitor or tourist without any proper knowledge of the history of Cambodia, while my colleague who organised the visit led the students. My visit to these two museums deeply affected my understanding of Cambodia’s past.

Tuol Sleng was originally a school building, that in 1976 was transformed into a prison for objectors to the Khmer Rouge. There are many rooms in this building, and there are different objects displayed in each room to show how it was used. One room has a steel bed at its centre; on the wall is a photo of the body of a victim laid on that same bed. In another room, there is a display of headshots of prisoners.

I walked through each room, listening to a narrative from an audio recorder in my ears. Visitors to the museum also have the choice to be accompanied by a museum guide.

Tuol Sleng was originally a school building, that in 1976 was transformed into a prison for objectors to the Khmer Rouge. There are many rooms in this building, and there are different objects displayed in each room to show how it was used. One room has a steel bed at its centre; on the wall is a photo of the body of a victim laid on that same bed. In another room, there is a display of headshots of prisoners.

I walked through each room, listening to a narrative from an audio recorder in my ears. Visitors to the museum also have the choice to be accompanied by a museum guide.

It was not long before I felt overwhelmed by the information I was receiving, especially regarding the torture. I could not take any more when I got to the room with the headshots of the prisoners. I saw sadness and hopelessness in their eyes. I decided to leave the room, and sat down in an open space to calm down.

After visiting Tuol Sleng, my students and I went to the Choeung Ek Genocide Center. It is an open field which, in the past, was used as a killing field for the victims of the Khmer Rouge regime. The victims were also buried in this field. As at Tuol Sleng, the Choeung Ek Genocide Center also provides a choice for its visitors, to listen to an audio tour, or ask a museum guide to accompany them. I chose to use the audio recording while walking through the field. During my walk, I saw some teeth on the ground, as well as some pieces of cloth from the victims’ clothes. After I walked through the field, I sat down on one of the benches in the museum.

Visiting these two museums gave me a narrative about the past in Cambodia during the rule of the Khmer Rouge. When I visited, I understood that this story was told from a particular perspective, as I knew that the Cambodian government had built them.

After visiting Tuol Sleng, my students and I went to the Choeung Ek Genocide Center. It is an open field which, in the past, was used as a killing field for the victims of the Khmer Rouge regime. The victims were also buried in this field. As at Tuol Sleng, the Choeung Ek Genocide Center also provides a choice for its visitors, to listen to an audio tour, or ask a museum guide to accompany them. I chose to use the audio recording while walking through the field. During my walk, I saw some teeth on the ground, as well as some pieces of cloth from the victims’ clothes. After I walked through the field, I sat down on one of the benches in the museum.

Visiting these two museums gave me a narrative about the past in Cambodia during the rule of the Khmer Rouge. When I visited, I understood that this story was told from a particular perspective, as I knew that the Cambodian government had built them.

The museum in Indonesia and the museums in Cambodia have at least three similarities: they were built by the ruling government, they were built in the exact location where the terrible events occurred, and none of them provide a space specifically for visitors to contemplate what they had seen. These museums can be understood as media utilised by the ruling government to build a collective memory of what happened in the past. The objects in these museums are curated, displayed, and narrated in such a way to present a singular truth, which the visitors should believe.

The three museums are located in the exact place where the events happened, which strengthens the creation of the collective memory. This, combined with the addition of atmospheric audio, stimulates the visitors’ senses so they feel as though they were there.

The three museums are located in the exact place where the events happened, which strengthens the creation of the collective memory. This, combined with the addition of atmospheric audio, stimulates the visitors’ senses so they feel as though they were there.

This strategy made my faith in these interpretations of each historical event that much stronger – I felt as though I had experienced the actual event at each of these museums.

The absence of a designated space for contemplation disallows visitors the chance to reflect and digest the information received during their visit. I discovered some vandalism at the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum – English curse words written over a photograph of Khmer Rouge leader Pol Pot.

I can only assume it was done by a foreign tourist. I felt like I understood the feelings of the vandal; this person was angry after going through the rooms at the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, and because there was no other way for them to channel their anger, they vandalised the photo. The question is, what happens next, after visitors feel angry?

The absence of a designated space for contemplation disallows visitors the chance to reflect and digest the information received during their visit. I discovered some vandalism at the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum – English curse words written over a photograph of Khmer Rouge leader Pol Pot.

I can only assume it was done by a foreign tourist. I felt like I understood the feelings of the vandal; this person was angry after going through the rooms at the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, and because there was no other way for them to channel their anger, they vandalised the photo. The question is, what happens next, after visitors feel angry?

Museums and art galleries have the potential for peacebuilding, but it is up to them to decide to take up the role. They have the power to design and arrange exhibitions in a way that contributes to the visitors’ learning process. There are two key things that museums and galleries can do to embrace the practice of peace education. First, they should provide a guide who can encourage open discussion related to the material on display.

The guide could not only explain the content, but also encourage a positive dialogue with the visitors by asking what feelings and thoughts they have about the exhibit, and how they might contribute to making a better future by learning from what is displayed. Visitors need to be prompted to connect the lessons from the exhibition with the possibility of peace promotion.

Secondly, museums should provide a safe space for visitors to contemplate and reflect after visiting the exhibition. Just as I experienced, visitors often require some space and time to channel the emotions that were built up during their time in the museum. An exhibition depicting violence will likely bring out sadness or anger in visitors, and they need to be allowed to process these emotions and leave feeling empowered to contribute to the creation of a better and more peaceful society by learning from what they have seen.

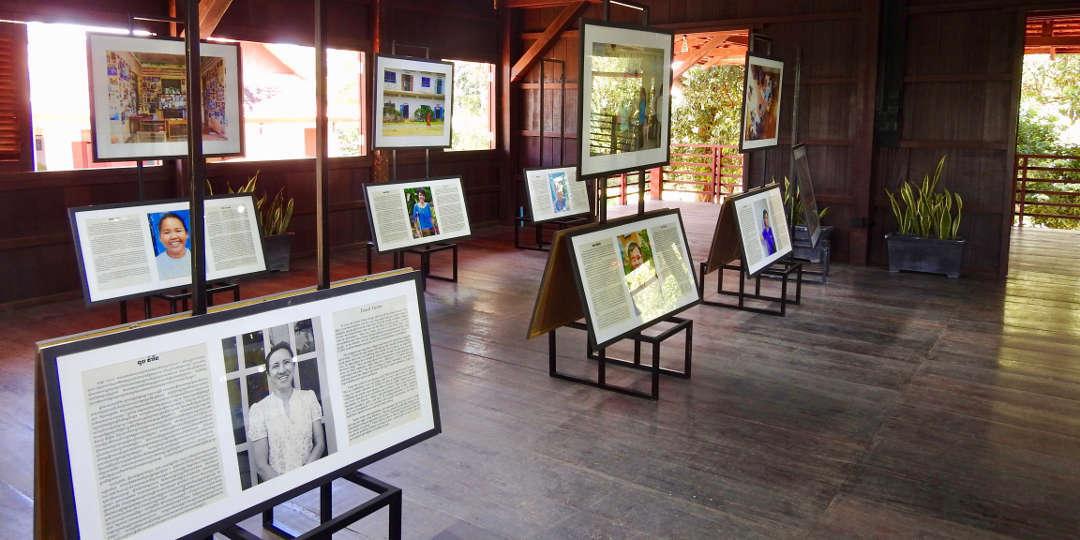

One institution that uses this approach successfully is the Peace Gallery in Battambang, Cambodia. This gallery provides information about the resilience of Cambodians, and the peace process in their country. Photos of various activities, as well as individuals’ stories, are used to show how Cambodian people displayed resilience during the time of conflict. Visitors to the Peace Gallery can take a guided tour, which presents the opportunity to have a dialogue about the past. There is a safe space for the guests to contemplate and express their emotions; the gallery also provides papers and crayons for visitors to write or draw their feelings and emotions. This gallery strives to build an open atmosphere in which to process the complex range of feelings that may arise.

One institution that uses this approach successfully is the Peace Gallery in Battambang, Cambodia. This gallery provides information about the resilience of Cambodians, and the peace process in their country. Photos of various activities, as well as individuals’ stories, are used to show how Cambodian people displayed resilience during the time of conflict. Visitors to the Peace Gallery can take a guided tour, which presents the opportunity to have a dialogue about the past. There is a safe space for the guests to contemplate and express their emotions; the gallery also provides papers and crayons for visitors to write or draw their feelings and emotions. This gallery strives to build an open atmosphere in which to process the complex range of feelings that may arise.

It is not only institutions that have a role to play: visitors also need to be responsible guests. Before visiting a museum, we should prepare ourselves, finding out the central themes and topics of the institution, and who has organised the exhibition. We also need to keep an open mind, while understanding that a museum is built and curated based on specific intentions.

My experience has shown how museums affected my understanding of the past. My closed mind as a child, and the manner in which I was taught about history, meant that when I visited a museum in Indonesia it simply confirmed the official story I had been taught. Being unprepared contributed to becoming emotional and feeling helpless when I visited museums of trauma in Cambodia, a feeling that was amplified by not having the space to reflect on what I had experienced there. I now understand that there are many versions of a single event, and I should be aware of that. I have also learned that museums are powerful and can affect our emotions.

Learning about history is essential for anyone interested in building peace. It gives us information on what worked and what did not in the past to create a peaceful society. Visiting museums and art galleries can be an empowering activity – we should leave feeling positive, with new ideas about what we can do to build a peaceful society.

My experience has shown how museums affected my understanding of the past. My closed mind as a child, and the manner in which I was taught about history, meant that when I visited a museum in Indonesia it simply confirmed the official story I had been taught. Being unprepared contributed to becoming emotional and feeling helpless when I visited museums of trauma in Cambodia, a feeling that was amplified by not having the space to reflect on what I had experienced there. I now understand that there are many versions of a single event, and I should be aware of that. I have also learned that museums are powerful and can affect our emotions.

Learning about history is essential for anyone interested in building peace. It gives us information on what worked and what did not in the past to create a peaceful society. Visiting museums and art galleries can be an empowering activity – we should leave feeling positive, with new ideas about what we can do to build a peaceful society.

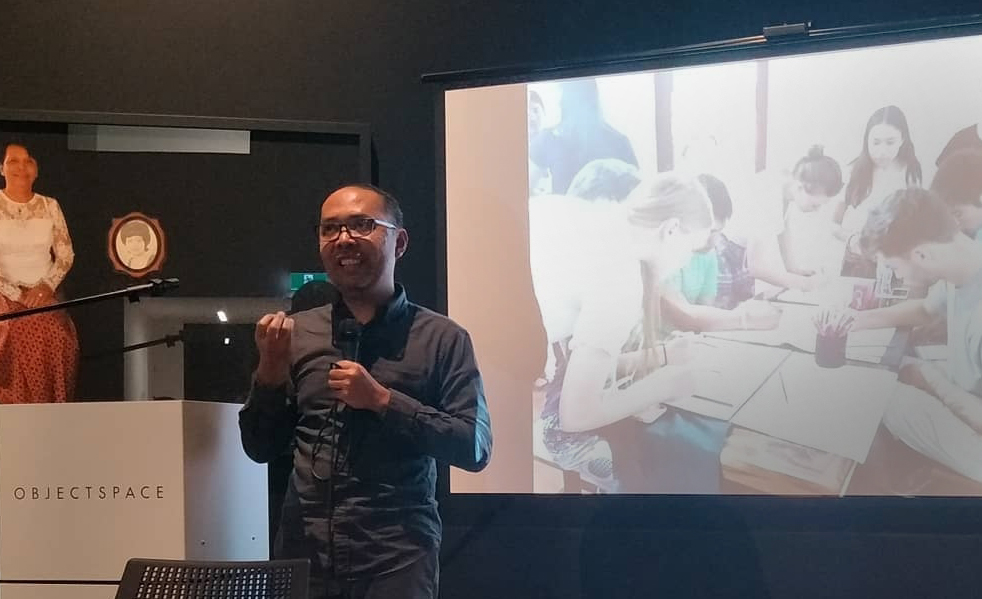

Dody Wibowo is currently conducting his PhD research at the University of Otago’s National Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies Te Ao o Rongomaraeroa through a Rei Foundation scholarship. His research explores factors contributing to school teachers' capacity in delivering peace education.

He has worked in several institutions, including Peace Brigades International, Save the Children, Ananda Marga Universal Relief Team. He has worked for UNICEF and the Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies in Cambodia.

Return to Journal